That posttitle wasn't supposed to sound so snotty, when I first wrote it. The conflict for me is not ivory-tower vs. ABC sitcom; rather, it's personal: a 50-something male vs. a rom-com featuring a heavily lipsticked 20-something actress. My resistance here is akin to my first reluctance to like Ally Condie's Matched series. I may get over this one, too. Forgive me, please, and read on.

Pygmalion enters world literature by way of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Ovid’s song of Orpheus

brilliantly understates the depravity of socially dysfunctional sculptor who

creates a lifelike form and successfully importunes Venus to animate it. Ovid’s

tale offers an infintely charming assertion that art can outdo nature. But, as

an account of human interrelationships, the Pygmalion story in Ovid is rather

disturbing. Reread Ovid’s account (Met.

10.243-97) and judge for yourself. Note that Ovid’s “ivory girl” never gets a

name and never even closely manifests a personality of her own. The physical

metamorphosis complete, Pygmalion’s objectivized wish-fulfillment becomes a reality by bearing his child Paphos. Pygmalion’s girl enters

the world stage a really beautiful nobody.

By the 20th Century, a rich

tradition had arisen around Pygmalion and his girl. Pygmalion by

George Bernard Shaw adapts the mythological narrative remarkably. Eliza

Doolittle surprises the Pygmalion figure, Higgins, by developing

character through their interaction. Pygmalion's ivory girl first acquired a name,

Galatea, when Rousseau (1770) “remythologized”[1]

the Pygmalion story and made the girl more than just a really pretty face; and

a string of comedies and tragedies and comic operas and works of many artistic

genres populated the European cultural landscape with the received myth.[2]

The rezeptionsgeschichte

of the Pygmalion myth has become wonderfully rich since Lerner and Lowe’s

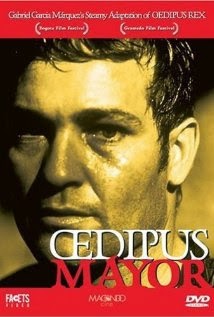

masterful muscial adaptation of the Bernard Shaw play as My Fair Lady. Dozens of apparent “Pygmalions” have filled the popular

cultural landscape, appearing in films from Weird

Science (1985) to Mannequin

(1987) to Ruby Sparks (dir. J. Dayton,

2012). V. Stoichita reads the Pygmalion myth convincingly into Hitchcock's Vertigo (1957). The Pygmalion narrative material represents

such fertile soil that any rom-com writer worth any salt seemingly cultivates a

potentially intriguing screenplay in it. And good writers — I like Zoe Kazan’s Ruby Sparks especially here — have grown

some very interesting adaptations, indeed.

|

| ABC's Selfie stars Karen Gillan and John Cho, premiering 30 September 2014. |

Selfie is a new

ABC romantic comedy that premiers 30 September. Emily Kapnek’s screenplay pairs

characters Eliza Dooley and Henry Higginbotam in an openly acknowledged

derivative of My Fair Lady. The pilot

aired on internet release in August. Reviews have ranged from

not-entirely-favorable to culturally-worth-watching. I missed the pilot,

although my mythologically aware daughter and research assistant both told me

to heed it for Mythmatters. Nevertheless, on the even of its premier, I now have

poured over the available clips at abc.com. From these I can surmise that Scottish

it-girl Karen Gillan plays Eliza and John Cho plays an updated Henry with some

unexpected (positive) consequences. There seems to be interesting romantic

chemistry between these two, and the transformation from Bernard Shaw’s London

to the social-mediaverse of Manhattan provokes thought.

What intrigues me most about Selfie are two considerations. First, readers of Mythmatters might

anticipate: Does this television program indicate anywhere within its narrative

fabric that it is in the Pygmalion (per se) tradition? That is to ask, in other

words, whether there is any moment within the program that manifests Emily

Kapnek’s awareness that her basic storyline derives ultimately from Pygmalion

and/or Ovid. I’ll be watching for this reason. The acknowledgment of

mythological ancestry still fascinates me. But secondly — and honestly more

interesting — viewers might seriously consider the narrative possibilities of a

Pygmalion turned utterly on its head. For, in what I can tell from watching the

previews, Kapnek’s Eliza far outstrips her narrative forebears by recognizing

early on her own vapidity. Dissed by the society that has welcomed her, this

Eliza understands that she must change, and she seeks out a craftsman who she

thinks can help. This may be the first moment in the Galatea rezeptionsgeschichte where the creative

impulse begins with the ivory girl and inserts the Pygmalion because she wants him there.

— RTM

From some reviews:

"Selfie is a very loose interpretation of the classic musical My Fair Lady, with “Eliza Dooley” an obvious reincarnation of Audrey Hepburn’s Eliza Doolittle. In My Fair Lady, the snobbish professor Henry Higgins (Rex Harrison) aims to take an unrefined flower girl (Hepburn), and make her presentable to London high society. Along the way, they both learn a lot about how the other half lives, and a stubborn attraction begins to grow between them.

"Instead of a snobbish professor, Selfie presents Henry as a marketing genius, who considers himself above Eliza and her social media obsession. He takes Eliza on as a project, hoping to turn her into a better human being. Because of the negative connotations of Eliza’s hobbies, she is the one who comes off as snobbish and self-involved to the audience, while Henry (despite the fact that he clearly feels superior to her) is the more sympathetic of the two.

"It is an interesting modernization of such a classic story, and the partial role-reversal opens up for a lot of new possibilities. We’re sure that Henry will manage to refine Eliza’s behaviour towards her fellow human beings, but he’ll probably also find that underneath her layers of makeup and/or Instagram filters, she’s got a lot to teach him, too."

OK: So it’s a My Fair Lady Remake. Is it a Pygmalion?

Verne Gay, “’Selfie’ review: What’s not to ‘like’? Plenty” Newsday 27 September 2014

‘"Selfie" is based on George Bernard Shaw's classic 1912 play, "Pygmalion," which has inspired other classics -- notably "My Fair Lady." Now, at this point, all obligatory references to classic plays and motion pictures must come to a screeching halt: "Selfie" is dopey."

Steve Haruch, “In ‘Selfie’, John Cho

gets an unlikely shot as a romantic lead,” NPR CodeSwitch, 28 Sept 2014

“The pilot, which premiers Sept. 30, is much better than its not-very-good name, sort of like the ‘90s Welsh band Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci.”

(later) …“That said, there's no getting around the fact that this is an update of an iconic character we've always thought of as British, and it's difficult to avoid the question: Can 'Enry 'Iggins be an Asian dude? (The answer in this case is yes, absolutely.) Sure, in a perfect world, there have been so many Asian-American male romantic leads that this casting choice is hardly worth noting as unusual or counter-intuitive, but as Cho himself acknowledges we don't live in that world. There's a reason we still have to call it "colorblind casting" instead of just "casting. Interestingly, the traits that make the classic Henry character tick overlap with commonly held views of Asian-Americans: nerdy, uptight, workaholic."

“Because he's a performer in someone else's script, Cho will probably face less scrutiny for molding Henry in his own image, even as Henry tries to mold Eliza in his. Because he's better known for who he is than what he is — a credit to the range and malleability of his craft — he brings less baggage to the role than another Asian-American actor might. … There's still some history to contend with, though, and if Selfie can find an audience, this revolution might be televised after all.”

Max Nicholson, “Selfie: pilot review” 19 August 2014 http://www.ign.com/articles/2014/08/19/selfie-pilot-review

“Loosely based on My Fair Lady (which itself was adapted from George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion), ABC's latest comedy series Selfie follows the life of Eliza Dooley (a modern-day version of Eliza Doolittle), a woman who's obsessed with all things social media.”

[1]

See Grafton’s Classical Tradition,

s.v. “Galatea” [M.Baumbach] and OGCMA

s.v. “Pygmalion”.

[2]

Reference works on the reception of the Pygmalion myth include A. Dinter, Der Pygmalion-Stoff in der europäischen

Literatur: Rezeptionsgeschichte einer Ovid-Fabel (Heidelberg: Winter,

1979); H. Sckommodau, Pygmalion be Franzosen

un Deutschen im. 18. Jahrhundert (Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1970); H. Dörrie, Die schöne Galatea: eine Gestalt Rande des

griechischen Mythos in antiker under neuzeitlicher Sicht (Munich: Heimeran,

1968); J.L. Car, “Pygmalion and the Philosophes,”

JWCI 23 (1960): 239 – 55; M.

Reinhold, CJ 66 (1971) 316 – 19; and

J. Miller, “Some Versions of Pygmalion,” in C. Martindale, ed., Ovid Renewed (Cambridge UP, 1988).